Vân

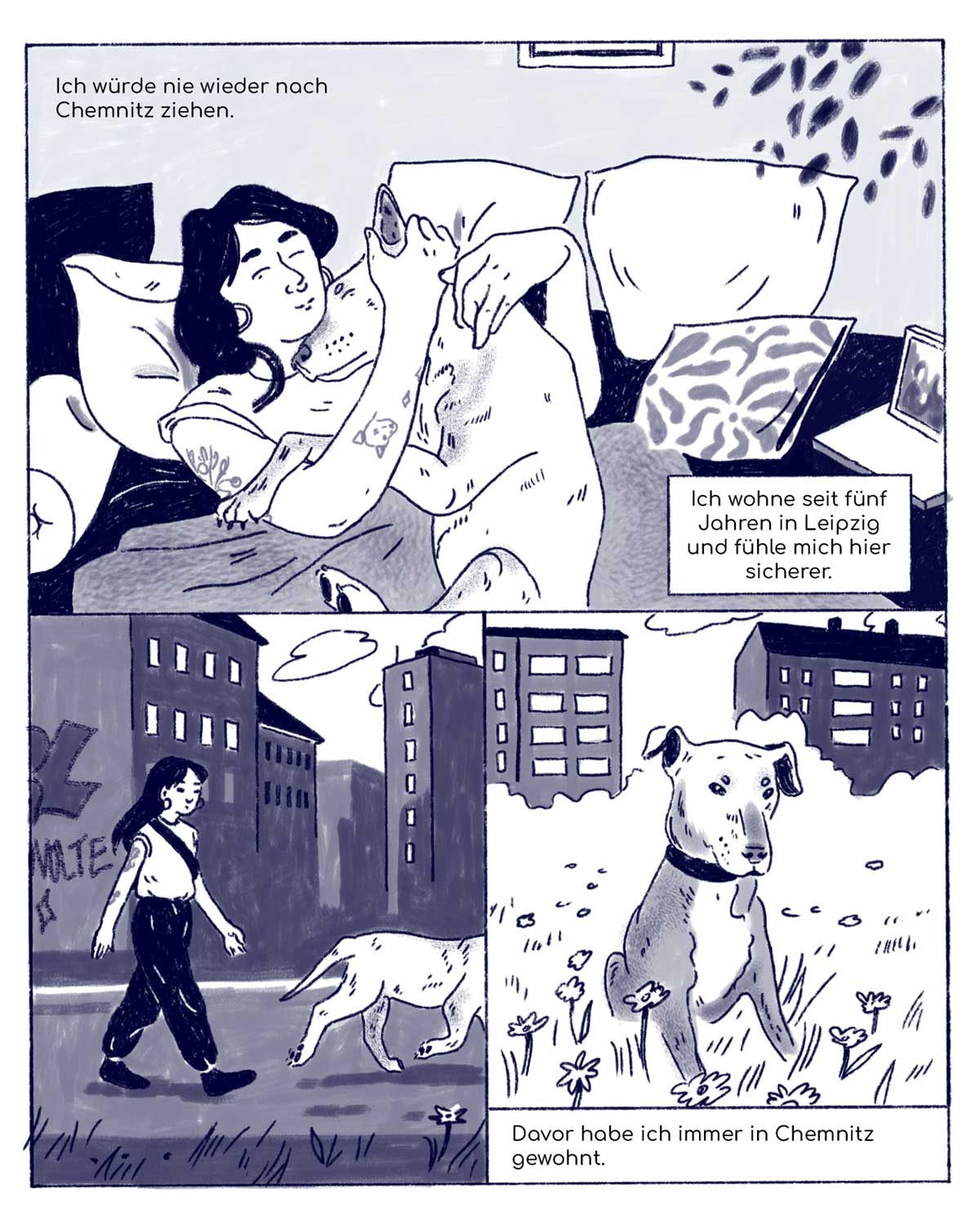

2018 verließ Vân Chemnitz. Ihre Geschichte verknüpft Alltagsrassismus mit der Arbeitsmigration vietnamesischer Vertragsarbeiter*innen.

There was a fruit and vegetable shop near the high school.

“Let’s go over to the F*dschi!” – Vân: “HEY! That’s a stupid word! Could you please stop saying that?” – “Do you want to go to F*dschi?”(whispering) After school, I was often home alone. I’m an only child.

I did my homework alone or started cooking.

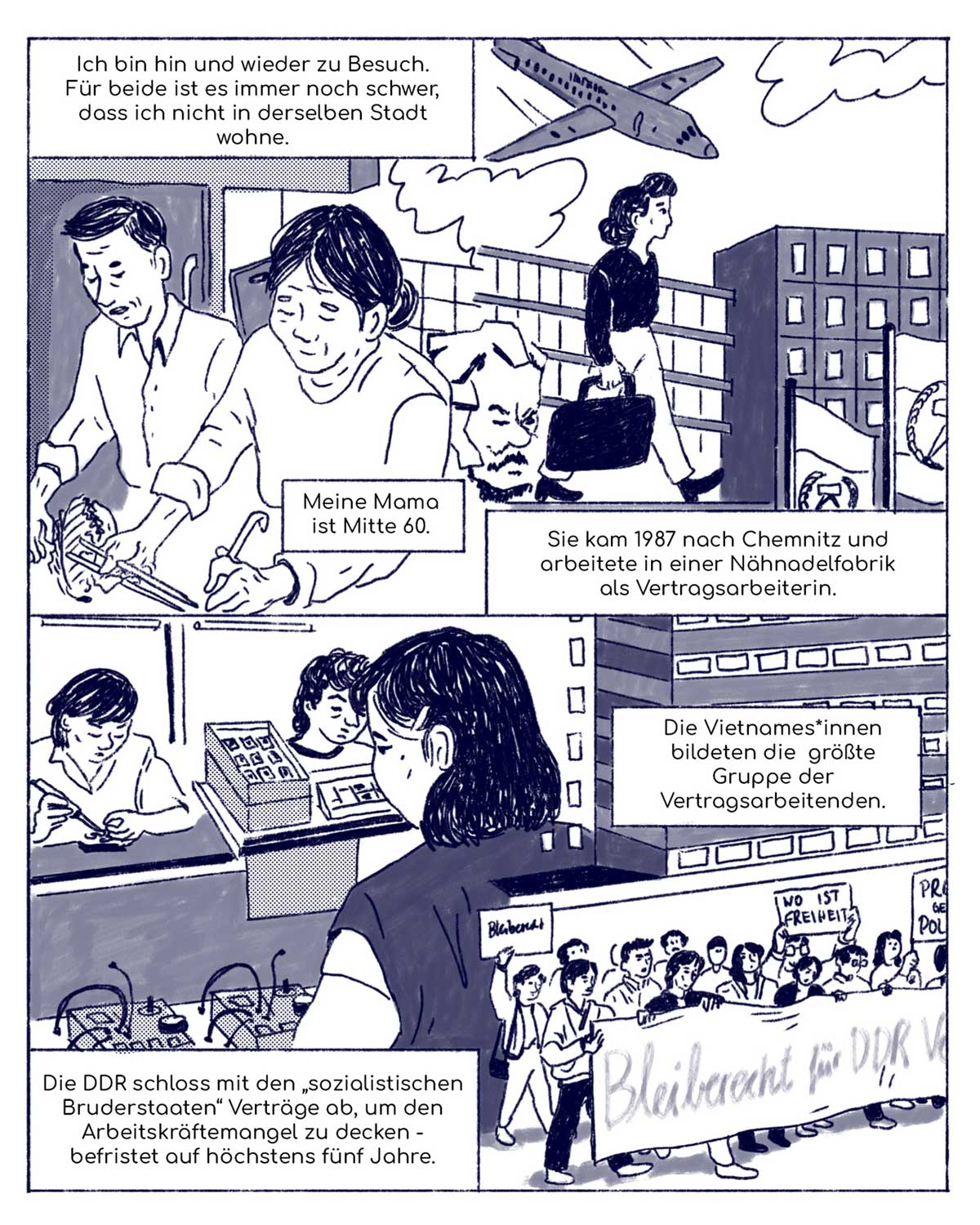

They were mostly given heavy and dangerous work under exploitative conditions. They weren’t allowed to choose their workplace or housing. My dad is in his mid-70s. He did an apprenticeship in East Berlin before returning as a contract worker in 1987. He worked as a translator in dormitories.

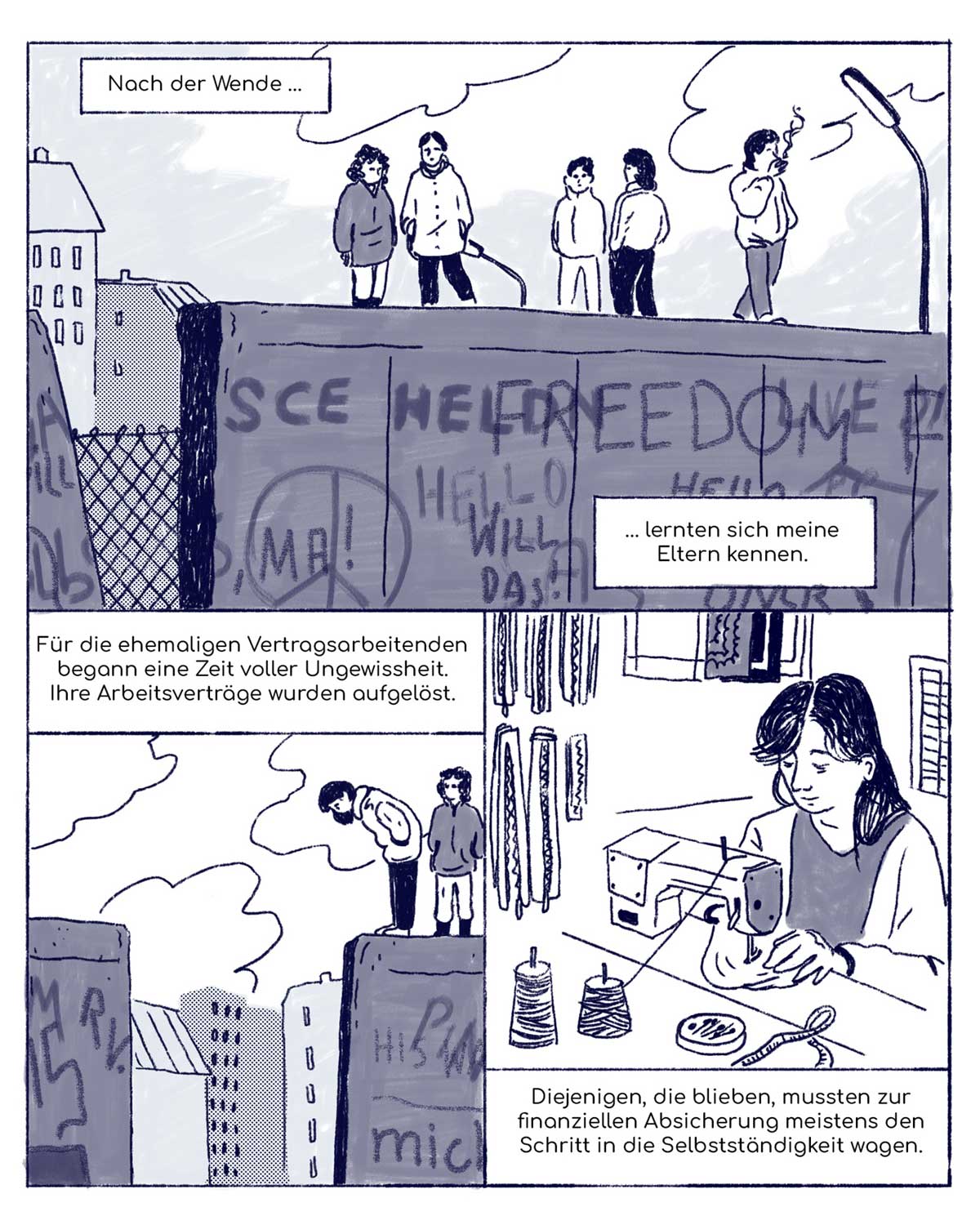

For the former contract workers, it was a time of uncertainty. Their contracts were dissolved. Those who stayed mostly had to turn to self-employment to secure an income.

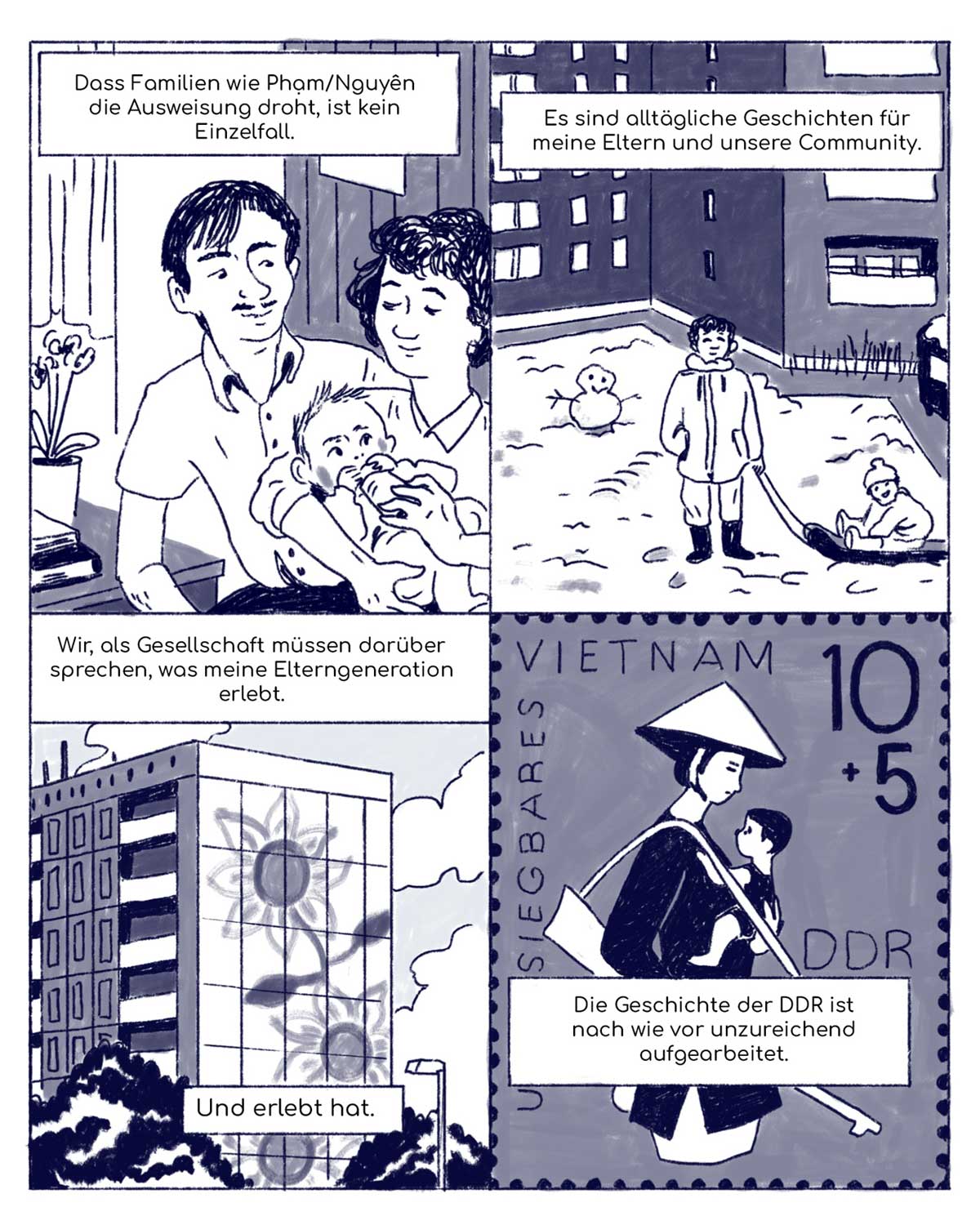

In 2023, the Phạm/Nguyên family from Chemnitz faced deportation after 35 years in Saxony.

Phạm Phi Son had come to the GDR in 1987 as a contract worker. He and his family were visiting Vietnam.

Because of a medical emergency, the family overstayed a deadline. As a result, they lost their residency rights.

I was shocked by this case. My parents’ generation not so much.

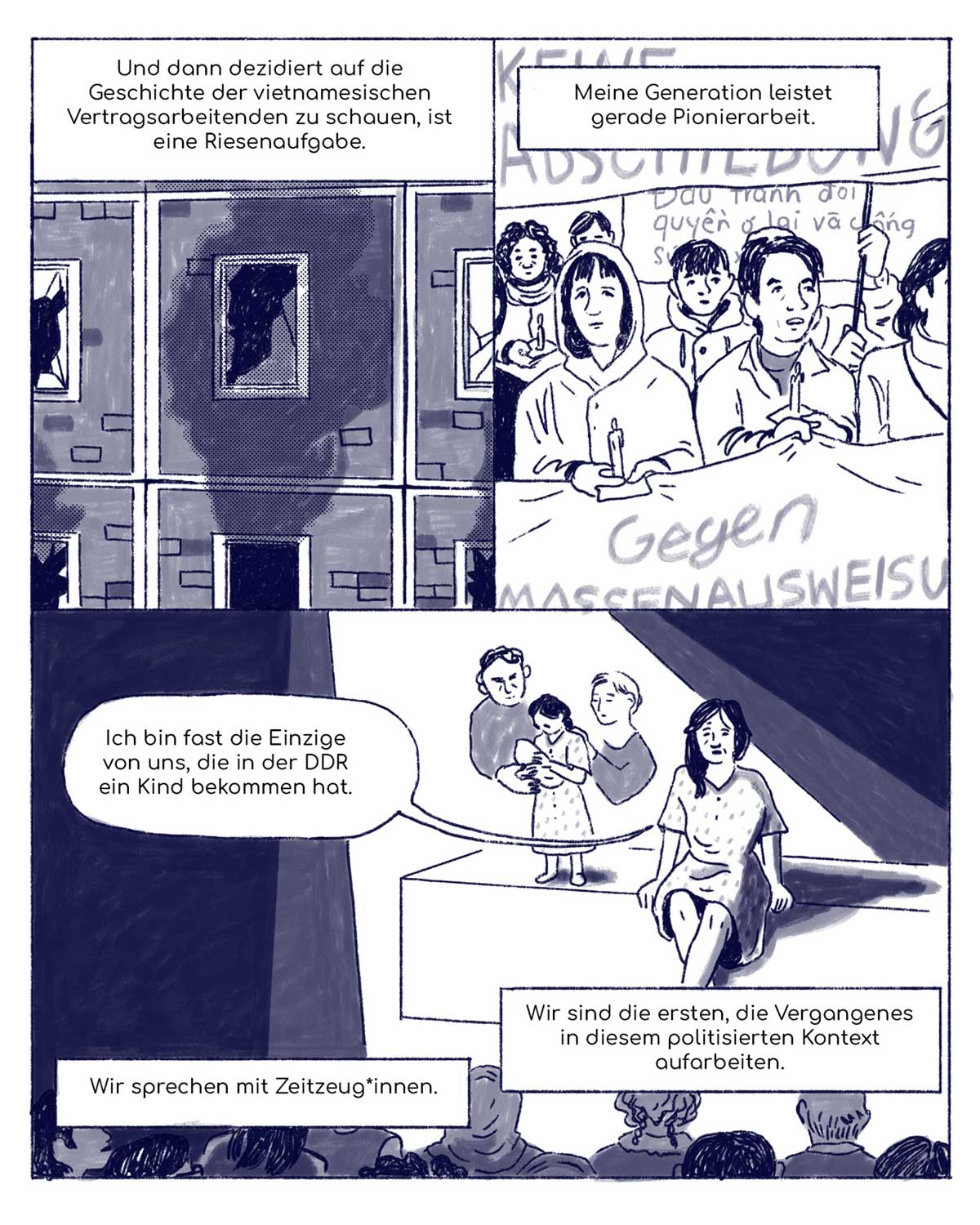

And looking specifically at the history of Vietnamese contract workers is an huge task. My generation is doing pioneering work right now. Actor: “I’m almost the only one of us who had a child in the GDR.” We talk with contemporary witnesses. We are the first to address the past in this politicized context.

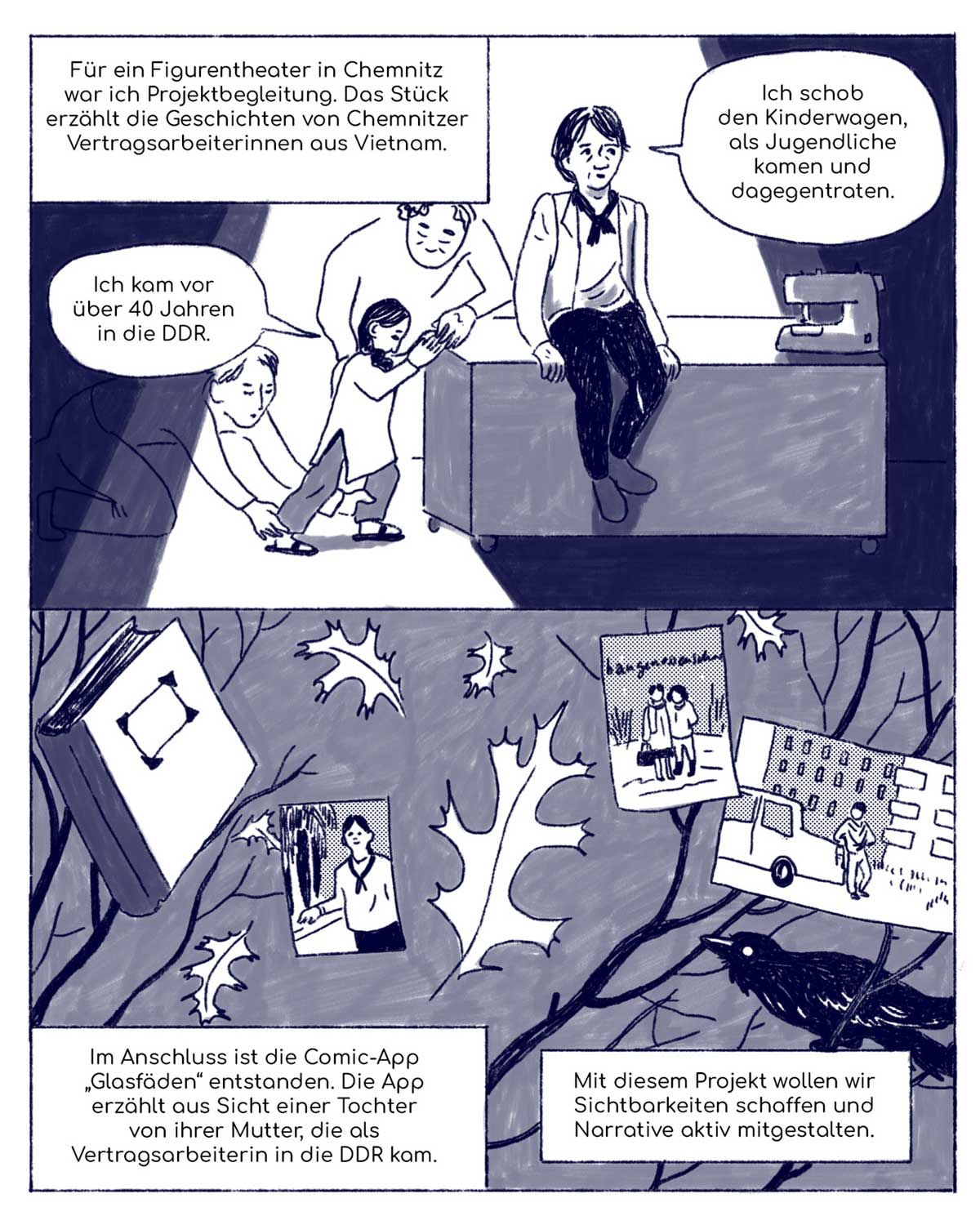

I worked as a project coordinator for a puppet theater in Chemnitz. The play tells the stories of Vietnamese contract workers in Chemnitz. Actors: “I came to the GDR more than 40 years ago.” – “I was pushing the stroller when teenagers came and kicked it.” This led to the creation of the comic app Glasfäden. The app tells the story from the perspective of a daughter whose mother came to the GDR as a contract worker. With this project, we want to create visibility and actively shape narratives.

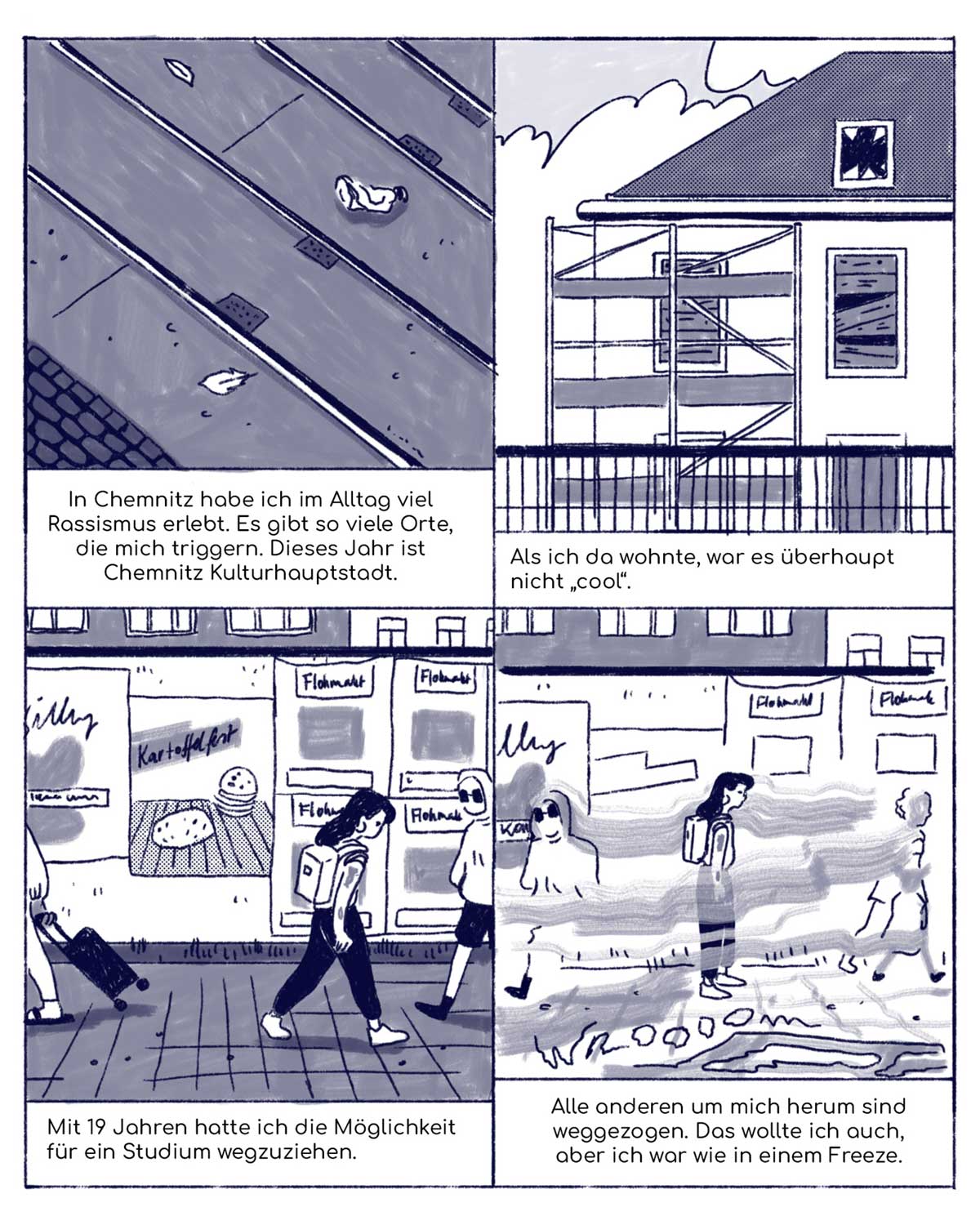

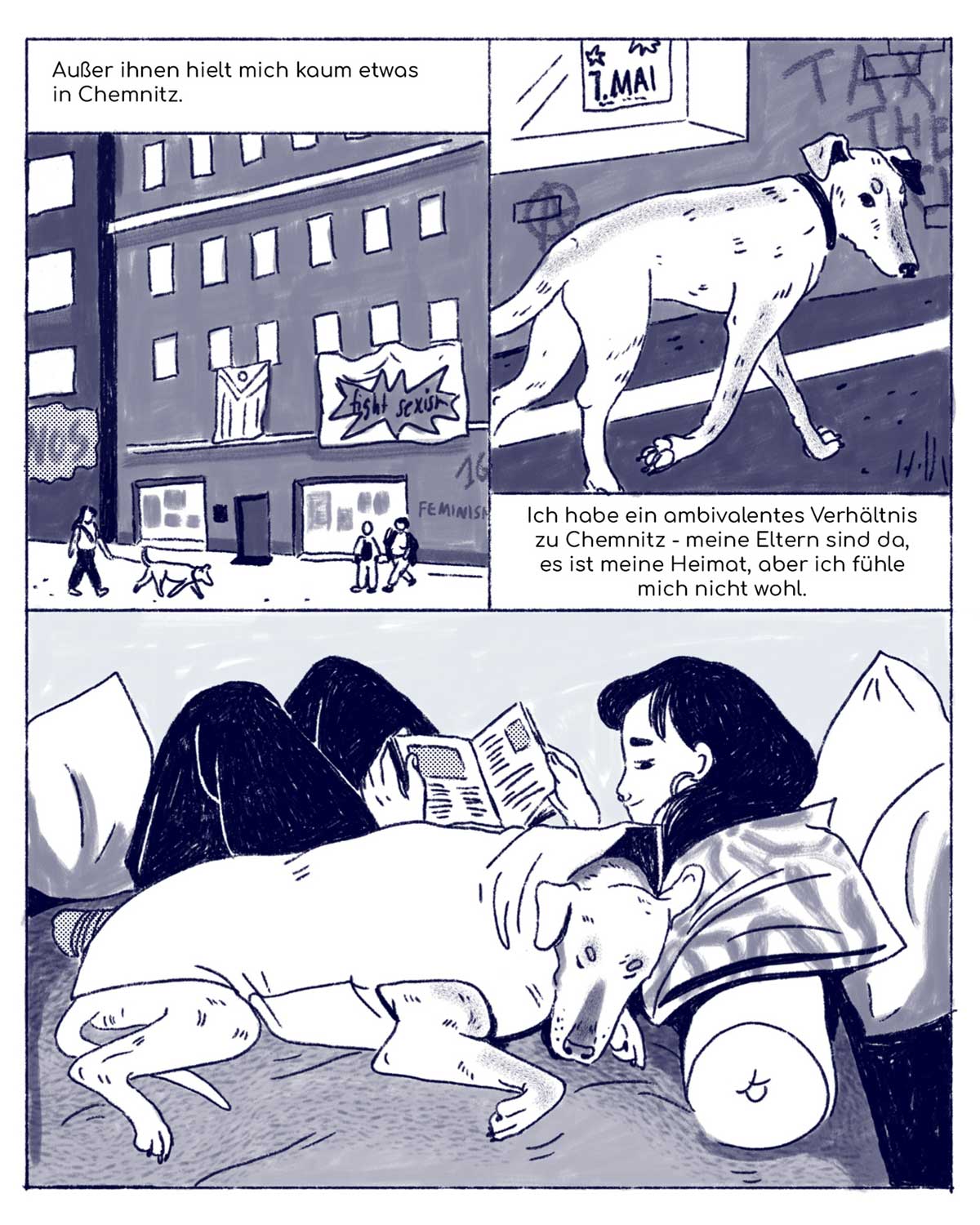

In Chemnitz I experienced a lot of everyday racism. There are so many places that trigger me. This year, Chemnitz is the European Capital of Culture.

When I lived there, it was anything but “cool.” When I was 19, I had the chance to leave for university. Everyone else around me moved away. I wanted to as well, but I was stuck in a freeze.

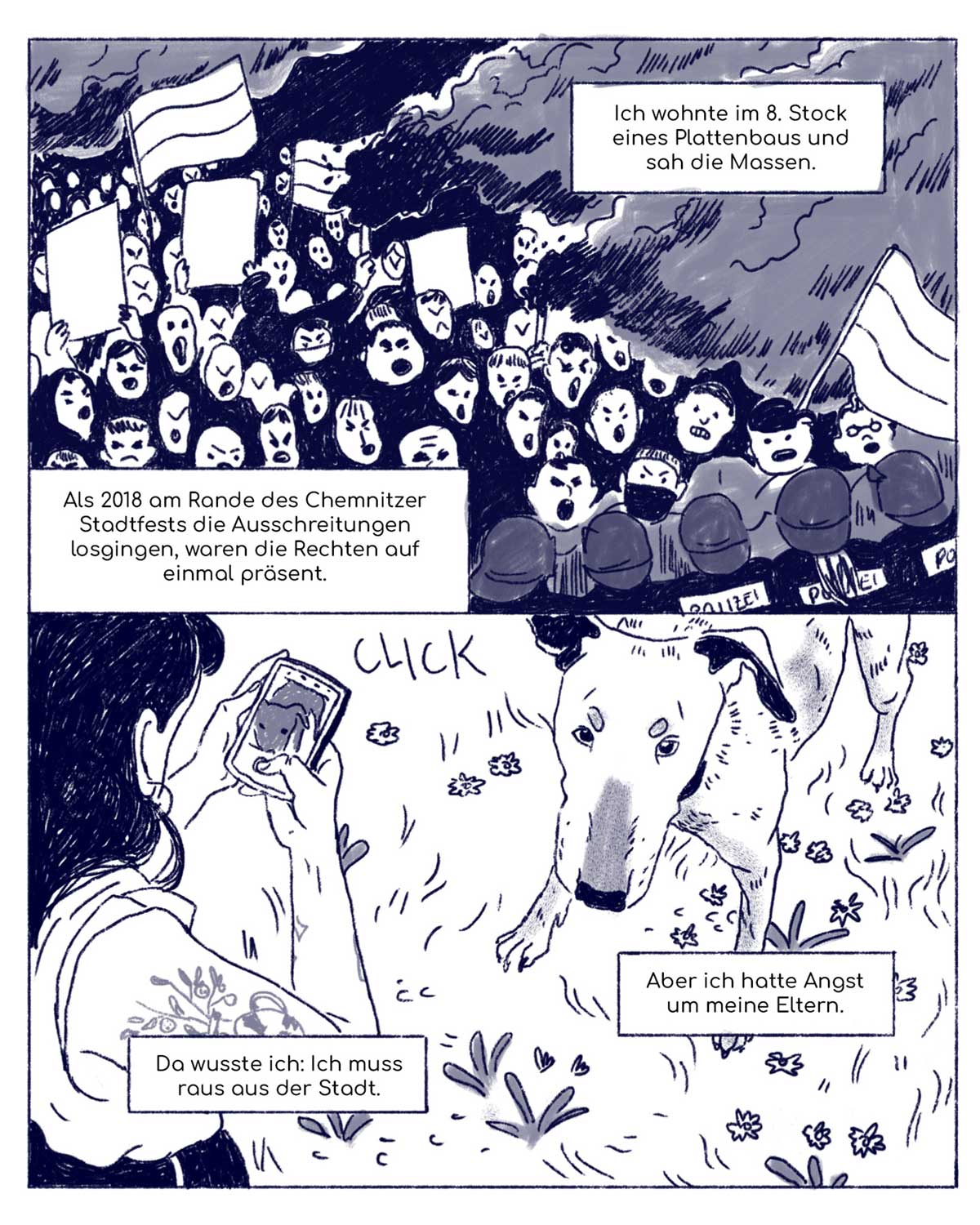

In 2018, during the riots on the sidelines of the Chemnitz city festival, the far right suddenly became very visible. I was living on the 8th floor of a prefabricated building and saw the crowds. That’s when I knew: I have to get out of this city.

But I was afraid for my parents. Besides them, there was hardly anything keeping me in Chemnitz.

Finanzierung / Sponsoring

Ein Projekt im Rahmen der Kulturhauptstadt Europas Chemnitz 2025. Diese Maßnahme wird mitfinanziert durch Steuermittel auf der Grundlage des vom Sächsischen Landtag beschlossenen Haushaltes und durch Bundesmittel der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien.

Mit freundlicher Unterstützung des Finnland-Instituts, Berlin / With the kind support of the Finnland Institut, Berlin

Wir danken unseren Sponsoren Volksbank Chemnitz, sowie der Deutschen Telekom!